A report by Common Wealth, Ashden Climate Solutions and Locality, with support from Power to Change. Produced in partnership with the Energy Learning Network (Ashden, the Centre for Sustainable Energy, Community Energy England, Community Energy Scotland, Community Energy Wales and Action Renewables in Northern Ireland).

The government’s Local Power Plan (LPP) aims to deliver 8 gigawatts of locally owned clean power by 2030 through thousands of community, council-led and shared ownership projects. It is vital to the government’s Clean Power Mission and to maintaining public support for net zero. It offers the government a unique opportunity to align its Clean Power 2030 and community agendas, helping to double the size of the cooperative and mutual economy, deepen devolution and create a legacy of community wealth, democratic ownership and energy justice at scale.

Despite strong public backing for local power — Common Wealth polling shows 62 per cent support for community owned energy, compared to just 40 per cent for private schemes — market failures and policy gaps continue to block viable local business models. At the same time, Social Market Foundation polling reveals deep scepticism: 48 per cent of people feel the transition is happening to them, not with them and 68 per cent expect net zero to increase their cost of living.

To close this divide and unlock the potential of local power, the LPP must deliver on its promise of eight gigawatts of local and community power by 2030. We recommend four key policy measures:

Without these reforms, the LPP risks reinforcing inequality, because it would have the effect of enabling only well-resourced communities to participate, leaving others behind. The political stakes are high: Labour has expended significant capital on GB Energy and the LPP delivering for ordinary people. Failure would pose a significant risk to Clean Power 2030, damage progress on the wider net zero agenda and undermine Labour’s credibility on community empowerment.

To meet the target of eight gigawatts of local power by 2030 in a way that works for communities, LPP delivery must rest on four pillars:

[.num-list][.num-list-num]1[.num-list-num][.num-list-text]Maintain the LPP target and investment, prioritising low-income communities and real community benefits.[.num-list-text][.num-list]

The eight gigawatts target and the £1 billion annual funding commitment — up to 40 per cent of GB Energy’s budget — are the foundation of a community-centred transition. Any delay or dilution risks stalling delivery and undermining public trust. We call on the government to:

[.num-list][.num-list-num]2[.num-list-num][.num-list-text]Ensure community energy business models are viable and can scale.[.num-list-text][.num-list]

The eight gigawatts goal of the LPP will not be achieved under current market arrangements. Meeting the full potential requires significant market intervention, to ensure community energy projects achieve a fair and stable price. To achieve this, we recommend government create:

[.num-list][.num-list-num]3[.num-list-num][.num-list-text]Invest in local capacity as core infrastructure for community energy.[.num-list-text][.num-list]

The LPP must invest in long-term, place-based capacity building — developing people, skills, partnerships and intermediaries, not just capital projects — to empower communities to lead the energy transition. This will require coordinated action across three levels:

[.num-list][.num-list-num]4[.num-list-num][.num-list-text]Establish a strategic partnership between GB Energy and communities.[.num-list-text][.num-list]

GB Energy can deliver scale and equity in the drive to Clean Power 2030 if it acts not only as a national investor and developer, but as a strategic partner to local communities. GB Energy should adopt a collaborative approach with a clear governance structure for the allocation of funding and powers, based on the principle that communities are often best placed to decide where and how projects should go ahead and how funding is spent. This should include:

Community owned energy has the potential to be a revival of a proud tradition of working people taking control of resources at a time of crisis. At the end of the eighteenth century, as war, enclosure, bad harvests and speculation drove food prices beyond reach, bread riots broke out across Britain. These were collective acts, led often by women, to demand fair prices and local accountability.

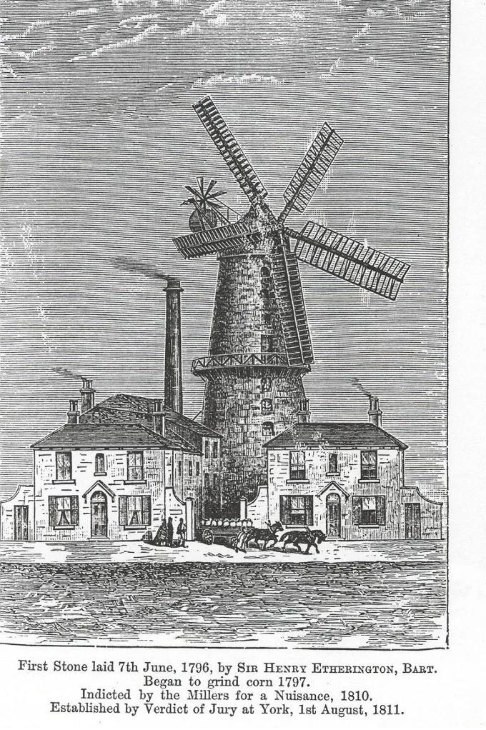

As food prices soared and hardship deepened, the poor inhabitants of Hull launched the Anti Mill Society, raising capital from their own pockets to build a co-operative mill. This brought infrastructure into the hands of ordinary people, harnessing the cutting-edge technology of the time — steam power. Their purpose, as they wrote, was “to make it convenient for the lowest capacity”. It carried on operating for a century as other mill societies established across the country, offering a grassroots alternative to the dominant industrial capitalist model, built on collective action, local ingenuity and for the benefit of ordinary people.[1]

[.fig]The "Anti-Mill" Flour Mill, Hull, 1795[.fig]

[.notes]Source: The National Cooperative Archive. Note: The "anti-mill" flour mill was one of several early English cooperative ventures set up by local people angry at the high prices charged by commercial millers.[.notes]

That spirit lives on. Today, a new crisis has taken hold — driven not by the price of bread, but by fossil fuel dependence and fuel poverty. Energy giants make record profits while millions face impossible choices between heating and eating. But once again, communities are responding — harnessing home-grown clean energy to forge a new future. Across the Humber in Grimsby, once the thriving heart of the world’s largest fishing fleet, a local power revolution is unfolding. While the town hosts the UK’s largest offshore wind supply chain, it is the quieter work of well-established community organisations that are building community wealth from the ground up. Grimsby Community Energy is funding and installing solar rooftops across the town — cutting energy bills, creating good local jobs and channelling surplus into a local community benefit fund.

Inland from Grimsby, Energise Barnsley is showing what is possible at scale — lowering fuel bills by up to 50 per cent in social housing through the UK’s largest council-community solar and battery project. Elsewhere, communities are repurposing old commons for a new era. In Enborne, Hampshire, land originally set aside as fuel allotments for the rural poor — part of a tradition of parish-held land used to meet basic energy needs — is being revived as a community solar farm. The site, still owned by the parish council, is now home to a project led by Calleva Community Energy, continuing the principle of local energy stewardship into the 21st century.

They are not alone. The latest figures show there are 583 organisations operating across the country in the community energy sector — returning £12.9 million to local economies and £13.8 million on energy bill savings, tackling fuel poverty and building wealth that stays rooted in place.[2] But the potential remains untapped. As the Co-operative Party’s “Community Britain” report argues, the energy system — like much of the UK’s economic infrastructure — remains structurally biased toward centralised, investor-led ownership.[3] Communities have too few rights, too little support and limited control over the assets in their neighbourhoods. The challenge now is to build an energy transition that is not only fast and fair, but democratic: one that gives people a real stake and say in the infrastructure reshaping their lives.

The Local Power Plan (LPP) must meet this moment. As one of five strategic functions of GB Energy, it can deliver the institutional architecture for energy democracy — supporting communities not just to benefit from, but to own and lead the energy transition, with a target of eight gigawatts of energy owned by local and combined authorities and community energy groups by 2030.[4] To succeed, it must be accompanied by enabling policies to ensure project viability, direct funding to areas of greatest need, invest in local capacity, embed community benefit into every project and forge a strong, strategic partnership with GB Energy and other institutions.

The UK’s transition to net zero must be driven with — not done to — people. That means communities hosting new infrastructure that delivers real, material benefits locally and giving people a meaningful stake in the transition. Yet, current public attitudes reveal a dangerous gap between ambition and participation. According to the Social Market Foundation, nearly half of people (48 per cent) feel the transition is happening to them, not with them.[5] The government’s own tracker shows 68 per cent expect it to increase their cost of living in the short term and 48 per cent in the long term.[6] This perceived lack of control and benefit risks eroding support for the level of ambition and pace of change required for decarbonisation.

Community energy — where people help develop, own and benefit from local energy assets and services — can help close this gap. Polling commissioned by Common Wealth shows community ownership significantly boosts public support for local energy projects — with 62 per cent backing a community owned scheme compared to just 40 per cent for a privately owned one (see Figure 1). Furthermore, opposition to community owned schemes was only 8 per cent compared to 21 per cent for private projects, amounting to a 35 percentage point premium in net support associated with community rather than private ownership (see Figure 2). A premium in net support was observed in every demographic group examined — including 2024 Reform voters — and was greatest for households with annual gross income between £20,000 and £30,000 (Figure 2).Over half of respondents said they would reduce their energy use to support a local project and meaningful numbers would contribute time (24 per cent) or money (14 per cent), revealing a powerful, but currently untapped, public appetite for collective action on energy when barriers like cost and time are addressed.[7]

[.fig][.fig-title]Figure 1: Community Ownership Takes Gross Support for Local Energy Projects over the 50 Per Cent Line for Almost Every Demographic Group[.fig-title][.fig-subtitle]Respective levels of support for community owned and privately owned local energy projects[.fig-subtitle][.fig]

[.notes]Q: To what extent, if any, would you support or oppose the creation of a community/privately-owned renewable energy project in your local area? [Asked to separate halves of the sample each for community owned and for privately owned; n=2415] YouGov, 22-24 October 2024.[.notes]

[.fig][.fig-title]Figure 2: The Net Margin of Support for Community Owned Local Energy Projects Is 35 Percentage Points Greater than for Privately Owned Projects[.fig-title][.fig-subtitle]Percentage point difference in net support for local energy projects between community owned and privately owned[.fig-subtitle][.fig]

[.notes]Note: Figures denote the extent to which net strong or moderate support for local energy projects is greater for community owned than for privately owned projects. Q: To what extent, if any, would you support or oppose the creation of a community/privately owned renewable energy project in your local area? [Asked to separate halves of the sample each for community owned and for privately owned; n=2415] YouGov, 22-24 October 2024.[.notes]

Community energy, then, is not a niche concern, it is a public mandate waiting to be acted on. It offers a rare opportunity to build consensus across political divides and to turn passive support for net zero into active local participation. But to fulfil its promise, the community sector needs strategic support, investment in capacity, skills, infrastructure and enabling policies — and a clear national plan to help it scale and diversify.

Labour’s LPP is a vital opportunity to do just that. Delivering a decarbonised power system by 2030 — Labour’s flagship Clean Power Mission — will require a rapid, unprecedented scale-up of onshore renewables. As the National Energy System Operator (NESO) warns in its “Clean Power” 2030 report, sustaining this pace beyond 2030 will require far deeper public engagement as deployment becomes more spatially concentrated and potentially more contentious.[8]

Without broad public consent, projects may face local resistance, legal challenges, or political backlash — threatening the pace of rollout and risking delays that we cannot afford. The LPP is therefore a strategic necessity in heading off resistance to clean power infrastructure and the broader net zero agenda; by ensuring all communities are provided the opportunity and the support needed to participate, own and benefit in the development of new community assets near to where they live. By embedding community ownership, shared benefit and public participation from the outset, the LPP can ensure buy-in for, and accelerate progress towards, the Clean Power 2030 targets.

The benefits of ambition are clear, but so are the risks of failure. Labour has staked significant political capital on GB Energy and the LPP ensuring ordinary people directly benefit from and control the energy transition. If the Plan falls short of its substantial promises, the political backlash and erosion of trust in Labour specifically would be substantial and electorally damaging.

Done right, the LPP can ensure every community has a stake in and something to gain from the clean energy future. It is how we turn national policy into a lived, local reality. It is how we build a just, democratic and enduring transition — one that carries the public with it every step of the way.

The LPP project is a collaborative initiative led by Common Wealth, in partnership with Ashden, Locality, Power to Change and the Energy Learning Network (ELN; comprised of Ashden, the Centre for Sustainable Energy, Community Energy England, Community Energy Scotland, Community Energy Wales and Action Renewables in Northern Ireland). The project aimed to shape a LPP that works for all communities.

The project combined polling, desk-based research with extensive engagement across the community energy and wider community sector. This included a series of meetings and workshops with key stakeholders including government officials working on the LPP and GB Energy, Community Energy England’s Experienced Practitioners Group, the ELN and wider community business and energy sector experts. We also drew insights from the evaluation of CORE and Community Energy Together and, in partnership with Locality, we conducted in-depth interviews with a diverse range of community organisations to understand how the LPP can deliver both climate action and lasting local benefit.[9]

The LPP is a historic opportunity to democratise energy ownership and ensure communities benefit directly from the energy transition. However, ambition alone will not deliver change. Without sustained, well-structured funding, the LPP risks reinforcing inequality — enabling only well-resourced communities to act, while those most exposed to the energy crisis are left behind.

Previous government programmes have too often failed to reach areas with the greatest need. Community energy remains unevenly distributed across the UK[10] and the Independent Commission on Neighbourhoods has identified “Mission Critical Neighbourhoods” in urgent need of targeted investment.[11]

To close these gaps and deliver on the LPP’s promise, we recommend:

The government should uphold its manifesto pledges to allocate 40 per cent of GB Energy’s budget — up to £1 billion per year — to the delivery of eight gigawatts of local and community power by 2020. This level of ambition and investment are foundational to delivering a publicly driven, community centred energy transition at scale.

Under previous levels of support, community energy projects often take years to develop and rely heavily on voluntary effort in their early stages. Uncertainty or gaps in support risk stalling projects, undermining confidence and deterring new entrants — particularly in communities with limited existing capacity. Maintaining long-term, predictable and flexible funding is essential to give local groups the time and stability needed to plan, build partnerships and sustain momentum.

In the immediate term, to bridge the gap until the full rollout of the LPP, the government should ensure the existing GB Energy Community Fund (GBECF) in England is increased and extended as soon as possible and should work with the devolved governments to ensure that there is continuity of financial support through their programmes, such as the Community and Renewable Energy Scheme (CARES) in Scotland. A hiatus in support risks breaking fragile project pipelines and disengaging committed communities.

To deliver a just transition, the LPP must direct investment toward the communities that stand to benefit most but are least equipped to participate. At least 25 per cent of all LPP funding should be ringfenced for priority areas,[12] using the “Mission Critical Neighbourhoods” in England and other established indicators such as Indices of Multiple Deprivation and fuel poverty data. However, targeting funding geographically is not enough.

To ensure maximum impact and accountability, all LPP-funded projects should be required to demonstrate tangible, measurable benefits to the community. These should go beyond direct carbon savings and environmental improvements and should address local priorities identified through genuine community consultation processes, including but not limited to:

Embedding clear but flexible community benefit criteria, with proportionate and manageable reporting requirements, will help build broad support for and incentivise wide participation from a variety of community organisations in the LPP while ensuring that public funding delivers meaningful outcomes on the ground — helping to secure local support, maintain public confidence and deliver on the government’s wider community, economic renewal and clean energy workforce agendas.

The LPP originally proposed up to £600 million in grants to local authorities and up to £400 million in low-interest loans to community organisations annually — a combined £1 billion per year to accelerate local power. The final funding architecture must both meet GB Energy’s new transaction requirements and the needs of communities. A flexible mix of grants and loans alongside clear community benefit criteria, as outlined above, should prevent money being diverted to plug holes in local authority budgets or support purely top-down delivery. The LPP should explicitly support a wide range of energy-related activities — including energy advice, retrofit coordination, community-led heat networks and smart local energy systems — not solely generation projects.

To support a thriving, diverse pipeline of projects, the LPP should offer a balanced package of financial tools, including:

However, in the absence of a guaranteed or preferential price for exported power — as outlined in the next section — many community energy projects, particularly those not using private wire arrangements, will also require capital grants to become financially viable. GB Energy equity stakes alone, which are likely to be offered on commercial terms, will not be sufficient to tip these projects into delivery.

Achieving the scale of community ownership promised by the LPP also requires urgent reforms to market and policy arrangements for small-scale renewable generation. The latest State of the Sector Report outlines how just 398 MW of community energy capacity has been built to date, after 15 or so years of the sector’s growth.[13] Delivering the eight gigawatts target in less than five years will require an order of magnitude increase in the rate of delivery of community energy projects. This clearly won’t be achieved under current market arrangements which typically restrict rooftop solar projects to those with an onsite power purchase agreement (PPA) or require larger scale renewables to secure a private wire connection (or some form of capital funding contribution).

Insights from our expert practitioner and sector stakeholder workshop, alongside wider research, show that unlocking a diverse range of business models is essential to scaling local power in a way that works for all communities. Currently, community energy projects struggle to develop a viable business model for the following use cases:

To meet these challenges, we outline the following policy changes that would provide the necessary support to ensure business models are viable and can scale:

The CfD scheme is the UK government’s flagship mechanism for supporting low-carbon electricity generation. It provides financial stability to renewable energy developers by protecting them from volatile electricity prices. Under the CfD, generators receive a fixed “strike price” for each unit of electricity. If the market price is lower, the market pays the difference.[14] If it is higher, the generator pays back the excess. Projects compete in sealed-bid auctions, where contracts go to the lowest-priced eligible bids until the budget is exhausted, with an inflation linked stable revenue stream, typically for 15 years.

Solar, tidal, onshore and offshore wind projects can bid for CfD auctions, with the projects separated into different “pots” dependent on the technology and its maturity. Offshore wind CfD rounds are also linked to specific zones of the seabed. There have been six “Allocation Rounds” for the CfD, with the seventh (AR7) due to be launched in August 2025. CfDs have proven a successful mechanism for driving the installation of renewable energy as they provide investors with price and therefore revenue stability.

However, renewable energy projects below 5MW are unable to access the CfD scheme and must instead engage in bilateral contracts with energy supply companies — known as power purchase agreements (PPAs) — or connect to onsite or nearby users of the power, via private wire arrangements. These agreements typically provide smaller scale projects with a much weaker business case than the CfD model, effectively locking out community scale <5MW renewable projects from the market.

If the government is serious about rapidly scaling community owned power — as outlined by Secretary of State Ed Miliband in the recent Power in Communities Report[15]— then this situation must change. The best way to meet the eight gigawatts target of the LPP is to bring in a viable price floor for all community owned renewable projects. The recent CfD AR6 delivered 15-year strike prices of £64/MWh and £61/MWh for onshore wind and solar at >5MW respectively. Recognising the additional community and local benefits of community energy projects, we recommend a “Community CfD” (CCfD) of around £100/MWh for community energy. This could emulate the Irish Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS) — RESS 1 and RESS 2 utilised a Community Preference Category (equivalent to UK CfD “Pots”), reserved exclusively for projects 100 per cent owned by the community, with full profits returned to them and exemption from bid bond or performance security requirements.

Adopting a price floor, rather than a competitive bidding process would recognise that community groups typically develop single-site projects and lack the resources of multi-site commercial developers. By gradually increasing the size of the CCfD pot, the government could control the number of projects which secure a CCfD, working towards the eight gigawatts 2030 target.

The Smart Export Guarantee (SEG) is the UK government's current scheme to support small-scale renewable electricity generators by paying them for the energy they export to the grid. It replaced the Feed-in Tariff (FiT) in January 2020, with a more market-based approach. The current SEG has significant drawbacks when compared to the FiT:

These drawbacks have meant community energy organisations have struggled to develop business cases for rooftop solar projects in locations where the onsite demand for energy at the point of generation is limited or unpredictable. This has led to a small niche of projects being viable, only where the solar system can be matched by predictable onsite demand. In many instances this has meant that systems have been sized at a much smaller scale than the available roof space — a wasted opportunity to maximise the capacity of renewable energy on the grid. In many other instances, projects have not gone ahead.

We recommend that the SEG should be reformed to require suppliers to:

This would ensure that behind the meter community energy projects receive a price from suppliers that reflects the true value of the power produced and would be unlikely to lead to increases in wider electricity prices, assuming that embedded generation has a lower system cost than larger projects connected to the transmission network (at the time of writing wholesale electricity prices are averaging around £85/MWh or £0.08/kWh).

Another critical business model for community energy is local energy markets. Local homes and businesses should be able to directly purchase locally generated renewable energy, underpinning project viability, cutting energy bills and bolstering local economies. These initiatives have the potential to match demand and supply in real time, within a primary substation area. Through smart Time of Use (ToU) tariffs these approaches can maximise the local utilisation of energy, reducing the need for costly grid upgrades and curtailment of surplus generation. Pioneering organisations such as Energy Local and Emergent Energy have demonstrated that these models are viable and can save low-income households substantial amounts on their electricity bills and enable the adoption of other clean technologies like heat pumps and electric vehicles.

However, the initial upfront costs of upgrading licensed supplier systems coupled with regulatory uncertainty puts off licensed suppliers providing services for local energy markets. High upfront costs and complex supplier agreements often make this model difficult to implement. Regulatory changes are needed to give local energy markets a firmer basis. DESNZ should give Ofgem a clear policy steer that local energy markets should be put on a more robust regulatory footing.

This should start with the implementation of the P441 modification, which would enable local energy markets within a primary substation area by allowing generators and consumers to settle energy trades locally before engaging with the wider electricity market. This has been in development for two years by a working group for Elexon, which oversees electricity trading arrangements and is regulated by Ofgem and does not require any taxpayer funding or legislative time in parliament. This should be followed up with legislative amendments for suppliers to service local energy markets if licensed suppliers fail to engage with local energy markets on reasonable terms.

At a high level, this legislation needs to define how the counterparty to domestic and commercial electricity customers can agree a tariff directly with one or more local generators (within the same primary substation area) for power consumed within the same half-hour in which it is generated, without the price being set by the supplier or a third party. The arrangement must deliver a price that provides a material reduction for customers and a material increase in income for generators by rewarding local balancing.

Delivering on the ambitions of the LPP will require more than capital investment — it demands sustained, strategic investment in the people, organisations and institutions. Community energy projects involve a wide-ranging skillset — from technical and financial, to legal, governance and community engagement. Building this capacity while balancing volunteer support with growing professional requirements will determine whether the LPP can achieve its ambitious goals.

Currently, many communities — especially those without experience in the energy sector — face serious barriers: limited early funding, lack of expert guidance and patchy local support. Even established organisations are under strain. A lack of capacity in local authorities — key delivery partners for the LPP — and shortfalls in policy coordination have further constrained progress. Without coordinated investment in closing these capacity gaps, the LPP could reinforce, rather than reduce, existing inequalities.

The LPP presents a unique opportunity to align the government’s communities and community energy agendas. Across the UK, thousands of established community organisations — from community centres and development trusts to faith groups and residents’ associations — already possess many of the foundational assets needed for energy projects: local trust, community engagement experience, asset management skills and deep neighbourhood knowledge. Many operate in precisely the disadvantaged areas the LPP must prioritise. By working through existing community sector networks and intermediaries, the government can leverage this existing capacity while building new expertise, creating a more inclusive and effective pathway to community energy participation. This will require coordinated action on three levels:

The government’s announcement that GB Energy Local will provide capacity and capability support for local and community renewable generation is a welcome step. This should be developed as a “hub and spoke” model, combining national coordination through GB Energy Local with deep local delivery through regional support structures.

At the national level, GB Energy Local should curate and integrate existing best practice into a coherent national offer. A wide range of resources, templates and guidance already circulate within the sector — developed by existing community energy intermediaries such as the Energy Learning Network, Community Energy England, Community Energy Scotland, Community Energy Wales, Net Zero Hubs in England, Climate Action Hubs and CARES in Scotland and others, as well as broader community sector support bodies. GB Energy Local's advisory service should be co-designed with and build on these foundations, to aid coordination and ensure additionality, while also developing institutional knowledge of community energy within GB Energy Local as a long-term strategic goal.

At the regional level, a complementary network of place-based, tailored capacity-building and support programmes should be funded — prioritising areas with limited existing capacity but high social need. For example, Community Energy GO offers free, tailored support to community groups just starting out or recently formed, with a focus on prioritising groups based in areas with little existing community energy activity or support and with higher levels of deprivation. These programmes should explicitly target both specialist community energy organisations and established community anchor organisations ready to diversify into energy projects. These regional support structures should offer:

Local skills development, including apprenticeships and curriculum integration in schools, should be a key focus, linked to the forthcoming Clean Energy Workforce Strategy.

By combining consistent national resources with regional, relationship-based support that works through existing community infrastructure, this model would create an accessible, effective route for all types of communities to engage with clean energy — not just those with existing energy sector experience.

Unlocking the full potential of local power requires strong, formal partnerships between community energy organisations and local authorities. Local councils are natural partners in the democratic ownership of energy — they hold public buildings and land, local knowledge, democratic legitimacy and convening power, while community groups bring trust, local engagement and delivery capacity. When aligned, these strengths create mutually reinforcing relationships that can accelerate impact and embed energy transitions in place.

With dedicated support and the right policy conditions, councils can act as powerful enablers of community energy — unlocking sites, brokering partnerships and coordinating long-term planning. These collaborations can take many forms, from pro bono support and access to public buildings and land to shared ownership and local asset transfers.[16] Yet many councils currently lack the staff capacity, skills, or clear policy mandate to support community energy effectively. The LPP should prioritise interconnected capacity-building within both local authorities and community organisations, empowering them to plan and act together. This means investing not only in technical support, but in the partnerships, processes and people that enable joined-up local energy leadership.

To support this, the government should establish a clear framework for collaboration, including co-designed strategies and shared delivery pipelines, defined roles for community energy in Local Area Energy Plans and Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies and long-term funding and a clear national mandate. Renewables on public buildings and land, backed by the GB Energy Solar Partnership,[17] should encourage community ownership to attract other forms of finance, maximise local benefits and ensure best value for the public purse. Reforms to procurement rules, shorter contract terms (e.g. three years to align with council planning cycles) and tailored finance — including low-interest loans and floor price guarantees — would support council partnerships.

The Treasury’s recent move in England to block school projects using PPAs, treating them as public debt, threatens to stall installations and should be urgently reversed to protect summer pipelines and uphold commitments to local power.[18] Clear guidance for local authorities and schools and a standardised PPA approved by government should be introduced. In Scotland, the procurement electricity framework agreement, to which most local authorities and public bodies are signed up to purchase their electricity, should be amended to allow an exception for purchasing community energy locally.

To ensure the LPP delivers at scale and in every community, there must be a coordinated national infrastructure for learning, knowledge sharing and peer support. Elements of this national infrastructure already exist, such as the Energy Learning Network, but are currently constrained in their ability to meet the scale of ambition in the LPP. A sustainably resourced national network — working in concert with GBE Local, regional support structures and local authorities — can provide the connective tissue needed to accelerate uptake, strengthen delivery and grow a more inclusive community energy sector.

Crucially, this network must be designed to support diversification and expansion of the sector, tapping into thousands of multi-purpose community organisations already operating in neighbourhoods across the UK. By investing in a national platform for sharing learning and best practice, the LPP can accelerate replication, improve project quality and ensure the benefits of the transition reach every corner of the UK. This is a low-cost, high-impact intervention that would unlock delivery by empowering the people and organisations already closest to the challenge.

The LPP must not stand apart from the wider national project of public power — it should be a cornerstone of it. GB Energy can and should act as a partner to local and community energy projects, enabling a whole-system approach combining scale with social ownership and democratic participation.

In Common Wealth’s model, GB Energy would operate under a public–commons partnership framework: developing large-scale generation, transmission and supply infrastructure while actively supporting decentralised, community-led energy initiatives. This means GB Energy is not just a central developer but a collaborator — providing technical assistance, finance and strategic alignment for projects under the LPP.

A joined-up strategy would ensure that public investment in energy builds long-term democratic capacity, not just kilowatts.

Community organisations, local authorities and GB Energy can and should work together to plan and deliver energy projects that meet both national decarbonisation goals and local social outcomes. In line with the Civil Society Covenant,[19] GB Energy should adopt a collaborative approach with a clear governance structure for the allocation of funding and powers, based on the principle that communities are often best placed to decide where and how projects should go ahead and how funding is spent.

The political value of this approach is also significant. For Labour’s LPP to succeed politically and practically, it must be part of a visible, grounded story of public power: one that includes large-scale national generation and local ownership alike, building a net zero future people can see and shape in their own lives. With the right design, it can be a flagship policy for a fairer energy system — one anchored in place, owned by people and delivering multiple benefits to communities in every corner of the country.

To successfully deliver the ambitions of the Local Power Plan (LPP), the government and GB Energy must commit to a comprehensive public engagement strategy that informs, empowers and involves the nation. This should form a core pillar of the forthcoming Net Zero Public Participation Strategy and align with the government’s pledge to double the size of the co-operative and mutual economy. Engagement efforts should focus on raising awareness of the benefits of community energy, increasing participation in project ownership and governance and ensuring that low-income and marginalised communities are actively supported to participate. This strategy must include:

Shared ownership is central to the LPP’s ambition of delivering eight gigawatts by 2030 and has the potential to be a critical component of the Clean Power Mission.[20] GB Energy’s founding mandate includes scaling shared ownership, but while there are successful examples in Scotland and Wales, implementation across England remains limited with developers often reluctant to offer meaningful opportunities for community involvement.

The government has just concluded a consultation on the Community Benefits and Shared Ownership for Low Carbon Energy Infrastructure. This includes proposals to strengthen the implementation of The Infrastructure Act 2015, moving from a voluntary to a mandatory model for shared ownership. The 2015 “Act” includes “provisions enabling the Secretary of State to make regulations which would give local communities the right to buy a stake in a renewable electricity generating station located in their community (‘the community electricity right”).[21] The LPP should deliver a step-change in shared ownership by embedding it within GB Energy’s delivery model and national clean power infrastructure. To do this:

This model builds on recommendations made by Community Energy Scotland, Community Energy England and Community Energy Wales in their April 2025 joint briefing to the UK Government on accelerating shared ownership.[22]

GB Energy should work with NESO and DNOs to reform the current “first come, first served” grid connection system. This must prioritise community owned and shared ownership projects that are “ready” and “needed” to meet clean energy targets and respond to local grid constraints. In particular, projects that will help to meet the eight gigawatts community energy target should be prioritised as “needed”. The recent increase in the Transmission Impact Assessment (TIA) threshold from 1 MW to 5 MW in England and Wales is a welcome step that removes a key barrier for smaller community and council-led projects, enabling more locally driven schemes to connect without disproportionate technical delays or costs. A similar review process should be undertaken in Scotland, where projects as small as 50kW in some areas still require a TIA.

Yet this reform does not address a deeper issue: most grid capacity “needed” for 2030 is already claimed —much of it by speculative or commercial projects. As a result, new community and public-interest schemes, even if ready to deliver and offering social value, may still be blocked. In line with recommendations made to the Government by leading community energy organisations, the government should formally designate community energy and shared ownership projects as “needed” for 2030 and reflect this in grid reform. Connection criteria must consider not just what is “needed for Clean Power by 2030”, but also what is “needed for the Local Power Plan”. Projects that deliver clear social and community benefit should be scored more favourably — ensuring they can “win on points” over purely commercial bids for limited grid access.

The authors have developed a companion report, based on detailed examination of community organisations’ experiences in developing community energy projects. “Clean Power = Community Power” sets out how the Local Power Plan can both help meet our net zero ambitions and build long-term community infrastructure.

[.image-cred]Cover image from Flickr/Ashden Climate Visuals (CC BY 2.0).[.image-cred]

[1] Steve Wyler, In Our Hands: A History of Community Business, Common Vision UK: 2017, pp. 58-62

[2] “Community Energy State of the Sector 2024”, Community Energy England, Community Energy Scotland and Community Energy Wales, 2024. Available here.

[3] “Power in our communities”, Co-operative Party, 2025. Available here.

[4] "Great British Energy founding statement", GOV.UK, 25 July 2024. Available here.

[5] Niamh O Regan, Jamie Gollings, “Whose energy transition is it anyway? The case of clean heat”, Social Market Foundation, 23 January 2025,. Available here.

[6] “DESNZ Public Attitudes Tracker: Headline findings, Summer 2024, UK”, GOV.UK, 29 October 2024. Available here.

[7] Adam Khan, “The Public is Enthusiastic for Community Energy”, Common Wealth, 2025. Available here.

[8] “Clean Power 2030: Advice on achieving clean power for Great Britain by 2030”, National Energy System Operator, 2025. Available here.

[9] Will Walker, Tim Davies Pugh, “Scaling community energy: four key lessons”, Power to Change, 31 January 2024. Available here.

[10] “Written evidence submitted to the ESNZ Committee inquiry on unlocking community energy at scale”, New Philanthropy Capital, January 2025. Available here.

[11] “Mission Critical Neighbourhoods Map”, Independent Commission on Neighbourhoods (ICON), 2025. Available here.

[12] “Making the government’s missions work in neighbourhoods: clean energy in every community”, Local Trust, 2024. Available here.

[13] “Community Energy State of the Sector 2024”, Community Energy England, Community Energy Scotland and Community Energy Wales, 2024. Available here.

[14] “About the CfD scheme”, Low Carbon Contracts Company, [undated]. Available here.

[15] “Power in our communities”, Co-operative Party, 2025. Available here.

[16] Mary Anderson, Ailsa Gibson, Rhona Pringle, “Collaborating on community energy: a guide for local authorities on working with community energy groups”, Greater South East Net Zero Hub, 2025. Available here.

[17] “Great British Energy to cut bills for hospitals and schools”, GOV.UK, 21 March 2025. Available here.

[18] “Treasury blocks school solar but summer installs may go ahead. CEE working on a long-term solution”, Community Energy England, 24 July 2025. Available here.

[19] “Civil Society Covenant”, GOV.UK, 21 July 2025. Available here.

[20] Jessica Hogan, Prina Sumaria, Fraser Stewart, Merlin Hyman, “Sharing Power: Unlocking shared ownership for a fast and fair net zero transition”, Regen, 2024. Available here.

[21] “Community benefits and shared ownership for low carbon energy infrastructure: working paper”, GOV.UK, 21 May 2025. Available here.

[22] “Community shared ownership: why guidance and targets are not enough”, Community Energy England, Community Energy Scotland, Community Energy Wales, 2025. Available here.